Emerging Evidence Linking the Gut Microbiome to Cancer

On November 30th 2022, the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S. approved a new kind of drug: a fecal microbiota product for treating antibiotic-resistant C. difficile infection[1]. In the near future, similar treatments derived from fecal bacteria and metabolites could help treat drug-resistant cancer.

The community composed of trillions of microorganisms residing in the gut — the microbiome — are increasingly recognized as modulators of gut, immune, and brain health. They impact host health through a variety of mechanisms including immune and endocrine modulation, vagus nerve signaling, and through the production of bioactive metabolites[2].

Recent improvements in sequencing and metabolomics technology has allowed scientists to investigate the role of gut microbes in cancer. Interdisciplinary collaborations across the world unite clinicians with bioinformaticians at leading research centers like APC Microbiome Ireland or the Knight Lab at the University of California, San Diego. By comparing the differences in gut microbiome between healthy people and cancer patients, individual bacterial strains and metabolites can be linked to the pathogenesis and treatment of certain cancers.

In the past decade scientists have found that multiple strains of gut bacteria are associated with colorectal cancer[2],[3]. Meanwhile, other cancers are also linked to the microbiome, which can impact the response to cancer drugs[3],[4]. For patients who don’t respond to immunotherapeutic drugs, but two recent clinical trials suggest a fecal microbiota transplant could boost the body’s response.

The gut microbiome in colorectal cancer

Since the gut microbiome is localized in the colon, a substantial body of research has investigated its links to colorectal cancer — the third most common cancer worldwide[5].

The gut microbiome is sensitive to the same lifestyle factors like diet which are important risk factors for developing colorectal cancer. These factors remodel the gut microbiome, affecting host inflammation and altering its metabolomic function[2].

These changes may increase the abundance of certain microbes associated with colorectal cancer including Fusobacterium nucleatum, Escherichia coli, Parvimonas micra, and Bacteroides fragilis[2],[6]. Based on this work, many scientists in 2023 are still testing whether a combination of these microbial biomarkers could detect cancerous polyps.

A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis found that the gut microbiome may be accurate as a diagnostic tool for detecting early-stage colorectal cancer (0.54 – 0.89 AUC), though there was substantial heterogeneity across different trials[7]. Adding the fecal metabolome into this prediction increased the diagnostic accuracy (0.69 – 0.84 AUC)[7].

The gut microbiome modulates host response to immunotherapeutics

Several studies since 2015 show that the gut microbiome plays an important role in determining a patient’s response to cancer drugs that target the immune checkpoint blockade (such as anti-PD-1)[8]. The gut microbiome’s composition and function may explain why half of patients with cancers like melanoma are resistant to these drugs[8].

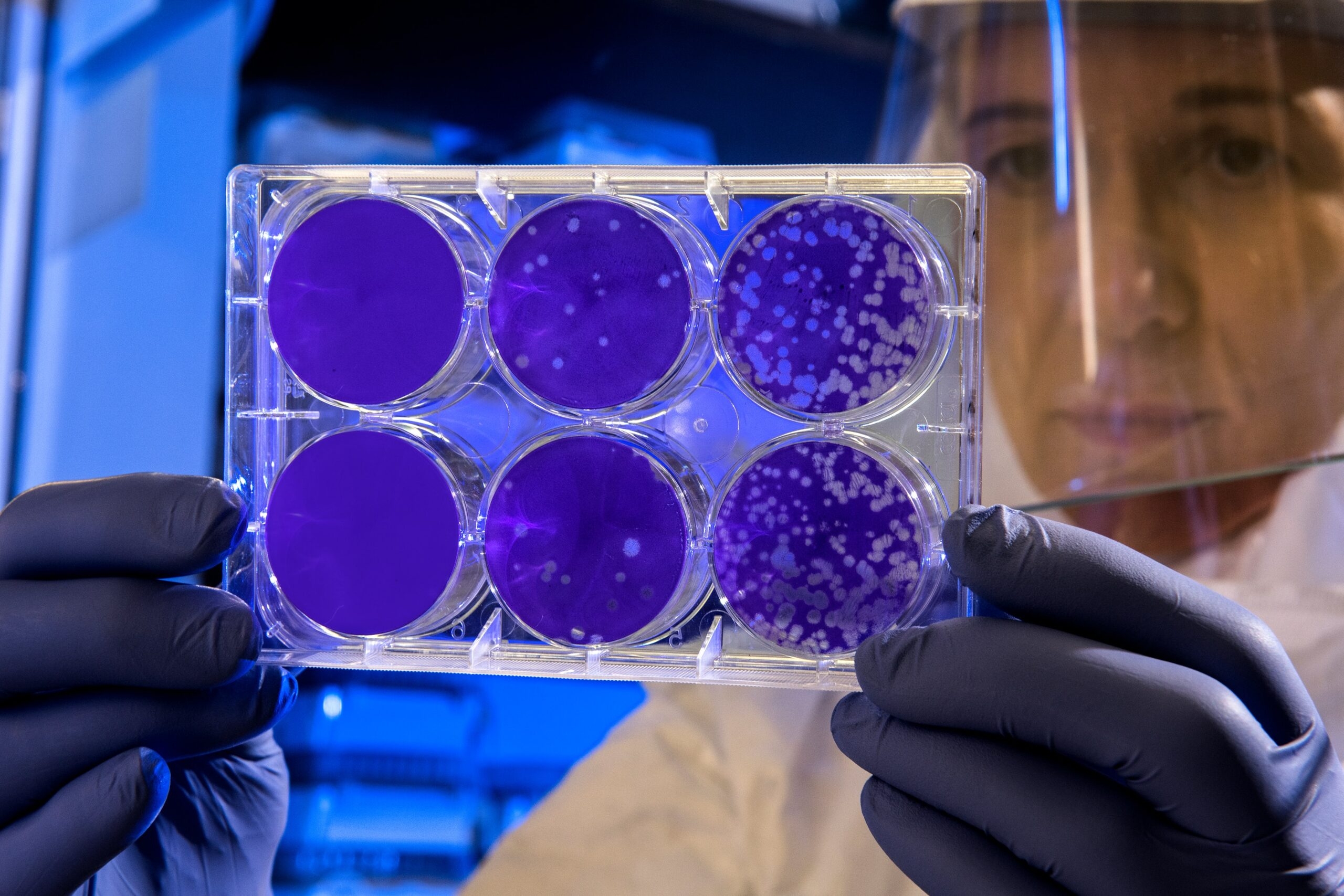

In 2021, two clinical trials tested this hypothesis. Fecal samples from melanoma patients that responded to anti-PD-1 drugs were transplanted into the patients who were non-responders. Across the two trials, this led to increased CD8+ T cell activation, and decreased the amount of interleukin-8-expressing myeloid cells[9],[10]. This resulted in an improved response to the cancer drugs in 30 to 40% of patients who were previously resistant to treatment[9],[10].

By characterizing the bacterial strains and metabolic signatures that enhance the immunotherapeutic response, interventions targeting the microbiome could be designed to augment existing cancer treatments[8].

What’s next?

Several early-stage startups such as Biome Diagnostics and Metabiomics are developing tools to develop fast, minimally-invasive screening tools for polyps. This may make it easier to identify colorectal cancer and intervene in the earliest stages of the disease. Other researchers are using synthetic biology to design bacterial strains as well as delivering drugs directly into the microbiome to enhance the response to cancer immunotherapeutics[11].

Meanwhile, clinicians are currently recruiting patients who didn’t respond to their cancer treatment for clinical trials to test whether a microbiota transplant could help. Trials around the world — including at Oslo University Hospital, Portland VA Medical Center, the University of Zurich, and Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal in Spain — are testing whether microbiota transplantation boosts immunotherapy response across different types of cancer.

The gut microbiome: A tool for diagnosing and treating cancer?

There are several bacterial species in the gut microbiome that are associated with colorectal cancer[7]. Already, diagnostic models are promising — creating a bloom of startups focused on developing these diagnostics[7]. Other clinicians are exploring the microbiome of people who don’t respond to cancer treatments to determine whether fecal microbiota transplants and products could boost the response[8].

Characterizing and modulating the gut microbiome in cancer patients may lead to new tools for improving screening and treatment.

In a 2022 Trends in Immunology review article[12], Clélia Villemin and colleagues from the microbiome phenotyping company Microbiotica Ltd highlighted the significance of the microbiome in cancer: “The strong influence of the microbiome on anticancer immunity has inspired a new line of bacterial-based therapies that can potentially reshape the immunological landscape around tumors, thereby enhancing responses to cancer immunotherapeutics.”

REFERENCE:

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Fecal Microbiota Product. (2022).

- Rebersek, M. Gut microbiome and its role in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 21, 1325 (2021). doi:10.1186/s12885-021-09054-2.

- Murphy, C.L.,O’Toole, P.W., Shanahan, F. The Gut Microbiota in Causation, Detection, and Treatment of Cancer. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 114(7):p 1036-1042 (2019). doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000075

- Nejman, D., Livyatan, I., Fuks, G., Gavert, N., Zwang, Y., Geller, L. T., … & Straussman, R. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type–specific intracellular bacteria. Science, 368(6494), 973-980 (2020). doi:10.1126/science.aay9189

- World Cancer Research Fund International. Colorectal cancer statistics.

- Wong S.H., Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(11):690–704. doi:10.1038/s41575-019-0209-8.

- Zwezerijnen-Jiwa, F. H., Sivov, H., Paizs, P., Zafeiropoulou, K., & Kinross, J. (2023). A systematic review of microbiome-derived biomarkers for early colorectal cancer detection. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.), 36, 100868. doi:10.1016/j.neo.2022.100868

- Park, E.M., Chelvanambi, M., Bhutiani, N. et al. Targeting the gut and tumor microbiota in cancer. Nat Med 28, 690–703 (2022). doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01779-2

- Baruch, E. N., Youngster, I., Ben-Betzalel, G. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 371, 602–609 (2021). doi:10.1126/science.abb5920

- Davar, D., Dzutsev, A.K., McCulloch, J.A. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 371, 595–602 (2021). doi:10.1126/science.abf3363

- Zhu, R., Tianqun L., Wenlu Y. et al. Gut microbiota: Influence on carcinogenesis and modulation strategies by drug delivery systems to improve cancer therapy. Advanced Science 8, no. 10 (2021): 2003542. doi:10.1002/advs.202003542

- Villemin, C., Six, A., Neville, B. A., Lawley, T. D., Robinson, M. J., & Bakdash, G. The heightened importance of the microbiome in cancer immunotherapy. Trends in Immunology. (2022).